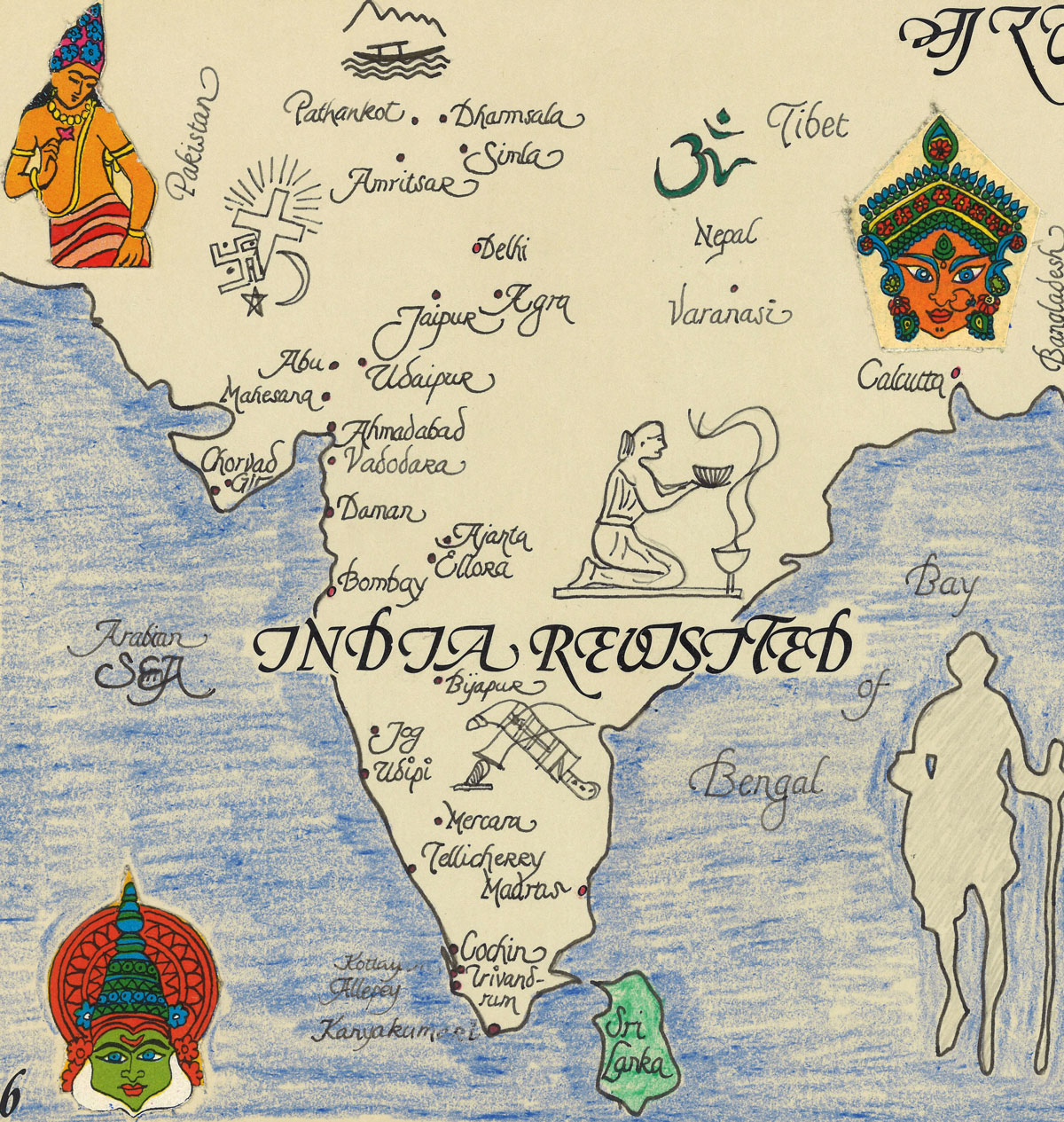

A Passage Through India

Notes from train journeys in the seventies

Every city and every town in India have a train station. And every train station is a bustling, chilling chaos of restless, skinny, screaming, and filthy individuals. For a stranger, an Indian railroad platform looks more like an incomprehensible dream from a distant world packed with running coolies and newspaper boys dancing between crumbly beggars, cupcakes, and holy cows.Every station feels like a hustle and bustle as if the hundreds of millions of people in this nation are living on this very platform. Alongside the 300,000,000 skinny and uncooperative sacred cows, India’s renovation ward, who graze on newsprint, cigarettes, and whatever humans prefer to waste.

In ancient times, in times long before the very first Viking, little or nothing was known about this enigmatic country beyond the widest horizon and the wildest thought. What was in India then, is still in India.

Despite the fact that an airplane now takes me to this vast ancient continent in a few hours, it is an old-fashioned world with a rich heritage that meets a Westerner. Where the presentation of Hindu teachings and Buddha impressions still make sure the dust from the past will linger on.

Three years after my first meeting with Hindustan, I'm again sitting in a train station. Again, I experience a wildness of screaming coolies, passengers, tea sellers, fruit traders, newspaper boys, invalids, blind people, conductors, tourists, bikers, and holy cows. Again, I experience a platform full of sleeping people wrapped up in rags and newsprint. Again, among dust and dirt from noisy steam locomotives. Nothings have changed. Only Indira Gandhi has had to pass her sterilization campaign and her slogan to a bunch of ancient orthodox oldies. But these things mean little to shoeshining boys, holy men, and poor peasants stressing along the platform.

The propaganda posters are still hanging there, as a reminder of India's strive to strengthen the national moral. The art of reading is a rare gift and most of the slogans are written in English, totally meaningless to most. «The Nation is on the move», I read in front of me.

Two trains are approaching the platform. One train is leaving. People panic back and forth. Young and old are shouting and screaming. Women, men, and children fight for seats. The strongest wins. Small children with brown and cheerful eyes, who, in all their innocence and theatrical splendour, beg for small aluminium coins. Paisa. I cleanse my conscience with Bernhard Shaw's thoughts about an account in heaven for those who give to beggars.

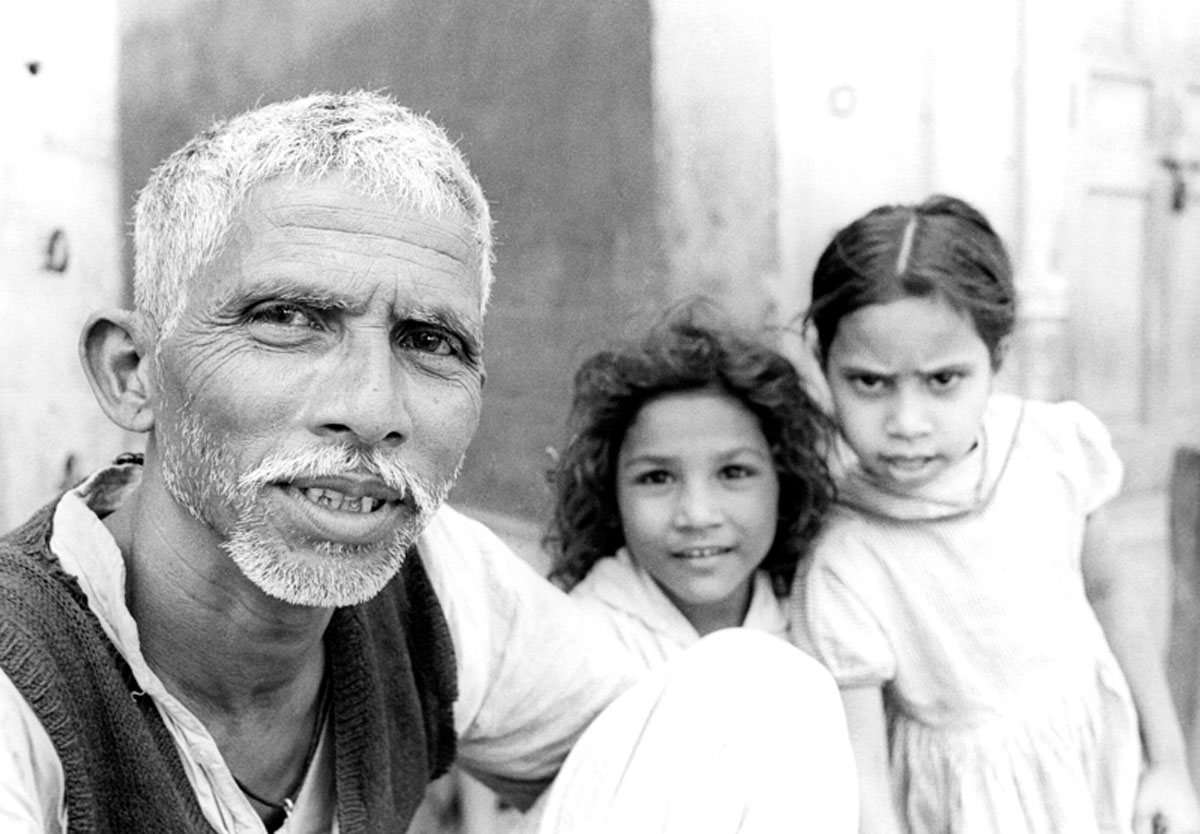

These are the same scenes and expressions I recognize from my previous visits. Women sitting alone, motionless on their tin suitcases. Women with children around on all sides. Yes, it feels like they are the very same women and kids who have been sitting here all the three years.

There are people everywhere. All over the platform: People, people, people. The crowd takes my breath away. Today 650 million. Tomorrow how many? In Kama Sutra's home country, the population increase is equivalent to the population of a small European town every day. That every time the planet Tellus spins around its own axis, as many new citizens are registered as in my hometown.

Abstinence is the old Morarji Desai’s philosophy. And his advice. The remedy that will save the continent from drowning in the result of an epidemic mating spell. Abstinence from both sex and alcohol. In a country where the cultivation of the phallic symbol is as sacred as the cow. Where condoms, spirals and pills are as distant as the Arctic waters and where antibiotics prolong the breathing a few more decades ....

When our calendar left the Victorian era, and slipped into the new century, a new-born Hindu boy could expect to be nineteen years old. Today, he will look forward to the age of 53 before the recalcitrant power of the reincarnation strikes.

My train finally rolls out of the station. Slowly disappear both sound and image and blends with impressions from the suburbs and the many small villages that pass by. I'm on my way into the mother of India.

At every little station people are waiting and waiting. Village people. Unemployed farmers on their way to the metropolis. People whose only property in life is time. At each station, a caravan of crumbly beggars enters the train with hands stretching out for a ration of mercy.

The express train is in no hurry. According to the plan, we will be in Lucknow tomorrow morning. 491 kilometres in twelve hours. The nation is on the move.

The compartment is jam packed. In the second-class compartment, people are fighting for oxygen. The hot summer night kills any thought of a pleasant journey. Second class is the class for the Indian middle class. And the unemployed academic class. With a few salesmen and some hippies as cargo, the train snails away competing with the ox carts. Jam packed as it is in the compartment, there is hardly room for thoughts and impressions. Curious and cheerful people want to know where I am from. Norway. “Which way?”

The poorest of the peasants travel on the roof. The bonded labourers do not travel at all. Corpulent rupee magnates enjoy the luxury of an air-cooled wagon in the company of perfumed pet dogs, condom agents and American NGO ladies with frizzle freeze hair styles and an instamatic camera. For a wealthy Indian and a western tourist, it is cheap to use the Indian Railways – Hindustan State Railways. The night's journey to Lucknow costs only twenty-two rupees, about two dollars.

The clock ticks on and the train takes us further into the dark night. Only broken by the whistle of the steam locomotive and carriages that bump into each other. At each station, the same. Over and over again. People who scream, fighting for seats and space. People all over. The voice of the tea boys stays with me long after the station has disappeared. Chay, chay, chay ...

As the night gets darker and darker, I travel deeper and deeper into the fathom of Mother India. The impressions from the last days in Delhi blends with railway stations, coolies, boy faces, donkeys, veiled women, and an ever-intrusive sleep to a fluttering lifeless dream without clues and safe delimitations.

Pahar Ganj is a noisy, dusty, frayed bazar area in Old Delhi. A living maze of stalls, tea houses, tailors, sex, and fart experts – and shabby hotels. Where long queues of stray dogs, coolies, and sacred cows move between semi-tall, fallow, and dark-leaved cement buildings. Sewage water, cyclists, horse cabbies, and annoying beggars fight for the space with crippled people who request a portion of compassion. People, animals, and objects are dancing in an untidy restless motion to the cacophony of Asian soap bubble music from the teahouses and the tiny stalls. There, inside the tea houses men with turbans and in pyjamas pants smoke their water pipes, untouched by the flies that swirl around like in a dense cloud. The atmosphere gives the nose a good job. A sweet-bodied stench of decay and indifference mixed with incense, spices, fat, and horse droppings drug the mind from a sober and objective impression. Indescribably exotic.

The everyday life of the bazaar is India's own supermarket. Real, spontaneous. Free from self-service, weekend offerings, and check books. In 45 degrees, hot goat meat hangs down from the butcher's rusty iron hooks. Vegetables traders tender their carrots and potatoes in a stench of holy cow piss and yellow-green amoebic dysentery. Through the whirlwind of flies, half-naked beggars and holy men, the housewives dressed in footy saris, with full lips, swollen waists, and a shopping cart, battle their way against overpricing. The Pahar Ganj Bazaar does not operate at regular prices. You bargain. Cash & Curry.

The bustling life goes on even into night's hours. The streets then turn into huge dorms. Wrapped in rags and newspaper headlines people calm down at night.

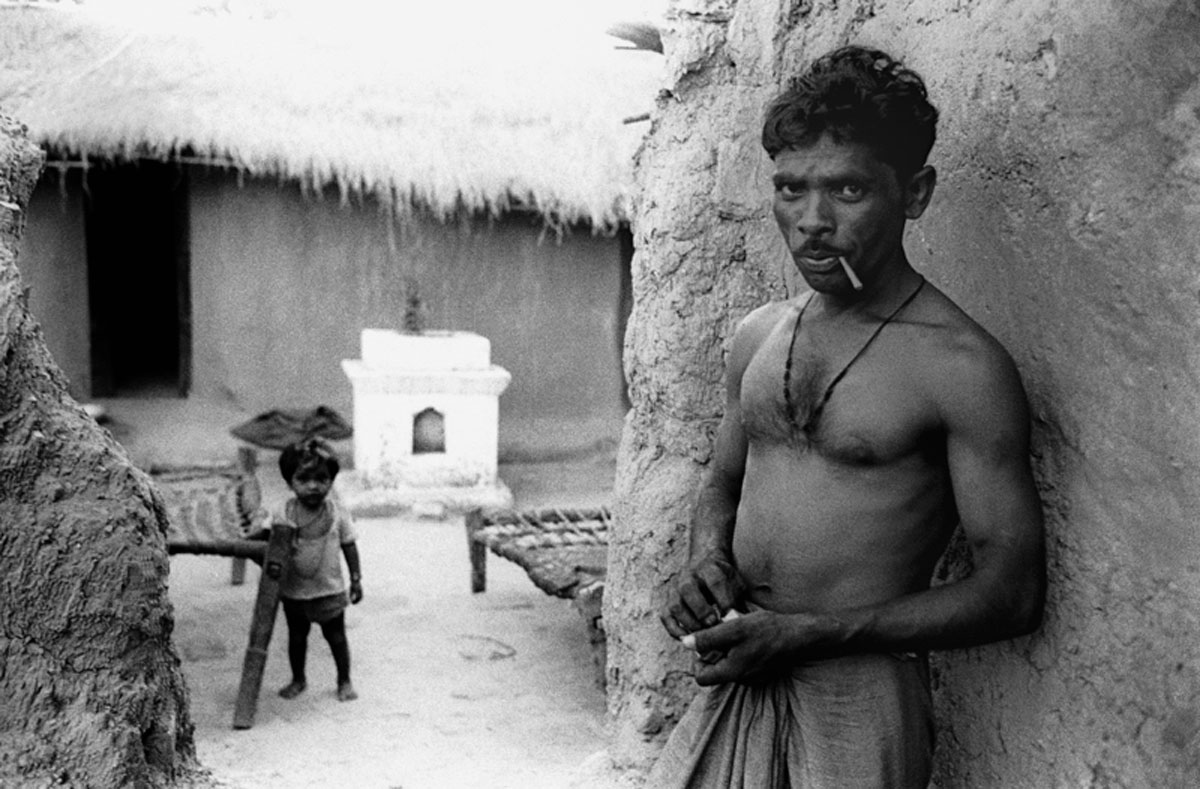

These are peasants and poor people who flow into the metropolis in search of something that can fill their bellies. Every tenth person in this vast country has no roof over his head, according to government figures. The beggars are a shame for the nation. But nothing is done. During the day they are hidden away, disappearing among the tens of thousands of others. At night, they are hidden in the darkness.

The darkness makes the streets totally inaccessible. Wherever I go, I stumble upon people. This is not a scouting camp, but a tragic reality. One evening I stood and let my eyes roll down the sidewalks of all the people sleeping on the pavements, and my eyes finally landed on one of India's huge propaganda posters: “The tax officer is your friend. Take advantage of his help.”

Several weeks later I'm leaving Sasan Gir in the state of Gujarat without being able to see the lions. I leave a peaceful little village in the woods where fifteen rupees have paid for evening dinner, lodging and morning tea for two people. The lions were too expensive to look at.

It's early morning, the sun has just climbed over the ridge and is spreading its rays between the trees in the woods. I take the shortcut through the forest to the station. An ox cart with people on the move moves slowly along the forest path. The train station at Sasan Gir is a small station at the end of the forest. It consists of a tiny station building where you buy a ticket, and a small tea shop with refreshments. Three trains a day provide entertainment in Sasan Gir. Three trains in each direction. Six arrivals and departures.

I can hear the train long before it comes within the reach of my eyes. Somewhere, far between the trees where the lights disappear, I can hear the sound of the whistle every time the driver lets the steam out. It's the same sound I remember from cowboy movies when action is expected. Here too, action is expected. The locals on the go suddenly get busy, pack up the cases and gather on the platform. It's still a while before the train arrives. The Indians sense of urgency is completely irrational, completely emotional, and totally devoid of reason and logic. It seems like panic in a way ...

The train is approaching. I can hear it long before I can see it. The coaches are almost empty, but people still panic around the steps so that they can secure a seat for themselves. They push and push and cannot wait until people get off before they squeeze themselves between other passengers and their baggage. Some pushes the luggage and the kids through the open windows. Twenty people fight for fifty places. Women and the elderly are the losers, the strongest wins a battle that is not even worth fighting for.

The struggle to survive is so ingrained in the average Indian that logic and common sense do not come into the picture at all. In a country where your next meal is not taken for granted, people do not learn to pay attention to each other but to grab anything and everything that might be useful. Those who come first to the dinner will survive.

I join some other travellers and a sadhu a holy man. He shows me pictures of Krishna, Shiva, and other Hindu gods, smokes his chillum, and looks content. He has long hair and a beard, and his forehead is painted in different colours – which symbolizes something I do not know what is. He is wearing a khaki green robe, and his material values consist of a flashlight, a walking stick, a Gita (Bible) and some religious images. Everything wrapped up in a cloth. He gets off at the next station.

The narrow-track train continues through the landscape. Even though it is December, the sun is already hot, and the people take to rest under trees and other shelters. They journey is slow. For each new neighbourhood, a new station. A new station with boys selling bananas and biscuits, whose sharp voices that advertise the goods cut through the air. Every new station is like a new play: people running back and forth, women who congregate, coolies carrying the rich people’s bags, small children selling drinking water at five paisa a glass, and bigger children selling everything else one can imagine. Everyone fights the customers' favour with loud voices. A few old men just watch, some women run inconsistently around, and boys just stand there looking at pale faces pushing their faces through the train window. They make faces and are having fun.

The conductor blows the whistle, waving the green flag and everyone who has stretched their legs rush to the doors. Mind your steps, doors closing. The train continues towards another station.

[December 1979]

“There is no such person in existence as the

general Indian.”

― E.M. Forster, A Passage to India