Across the Afghan desert

Excerpts from my diary in the seventies

The road from Kandahar to Herat stretches across endless deserts, where the only thing the eye can enjoy is huge sand dunes, a hot burning sun and some dried up river beds. It is November, it is still hot in Kandahar and it has not been raining for countless months. What are big, wide and powerful rivers in March and April is now at best a one-inch wide embarrassing little stream. When the snow melts, the rivers are many, witnessed by the many bridges, bridges that are now silent, lonely and almost without meaning. But the spirit, the soul, and the purpose of the bridges change when the enormous spring rivers enter early in the year.

There are miles between each village. They are few on the long stretch, and small. There is very little to sustain a life out of here, the few villages seem brown, poor, without life. Closer to Herat, the road goes up in the mountains, but it is still desolate. Great mountain ranges, high peaks, but still desolate. The only sign of life is the clay of the nomad caravans. Collections of large black tents, camels and sheep. At dusk, a fire or two lights up to warm. It is cold in the mountains at night.

Kandahar does not have much to offer a traveller. The hot and dry air alone is enough to send him off. The greatest impression the modern Kandahar has given me is undoubtedly the indescribable and deliciously apple pie from Your Bakery in the central square. Basically, a bit comical to be caught by an American pastry shop in a city in one of the world's poorest countries. But the reality is that in the old-fashioned days women were stoned and the throat of murderers were cut in front of the face of hundreds of excited spectators, here at the square in front of Your Bakery.

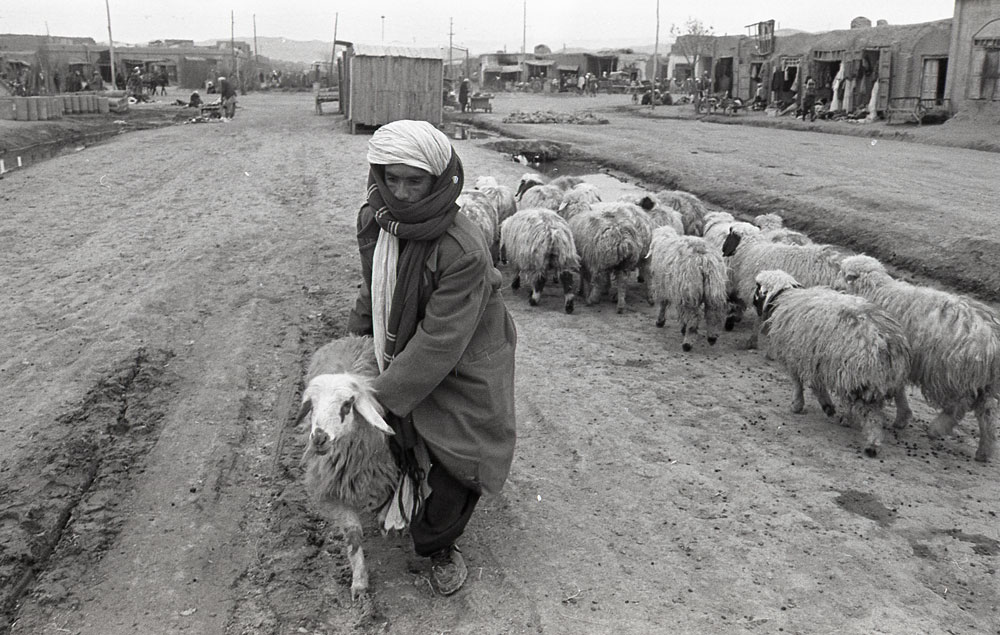

Kandahar is a modern Afghan city that strives to make itself disciplined. The traffic policeman makes every effort to get the traffic of donkeys, horseback riders, camels, cyclists and buses to smoothly float by.

That said, it's hot, incredibly hot, even though the calendar reads November. I restrict my strolls to the early mornings and afternoon hours. Despite the lack of tourist attractions, it is interesting to walk through the bazaars. It's busy. Everything is just so different from what I'm used to. There are people, animals and flies everywhere. Kitchen utensils, cement, tea, radios, bread, meat, fruit, carrots, and sheep are sold here. Often over a cup of tea, the Asian way of doing business.

Dust. Dust. Everywhere it swirls up from the street every time a horseback or bus runs by. It swirls where it is loaded and unloaded, with heavy bags filled with potatoes, vegetables and fruits are carried around. Afghanistan is a fruit garden. Lovely fruits. Melons of all colours and shapes. Large melons. Small melons. Apples, pears, grapes, pomegranates, apricots. And nuts. Pistachio nuts, walnuts, hazelnuts, peanuts and other nuts. But the season ebbs out. There are no longer any melons. The apples are spotted. The grapes are small and rotten. The pomegranates have cracked. Two to three weeks earlier I would have drowned in fruit, all of them delicious fruits. From now on it is the time of dried fruit.

Even though it is hot, there are parks, trees, and flowers. The city is green, as opposed to the brown desert that surrounds the city. Here is water. That gives life to plants, trees, animals and humans. That gives life to a small society of something over a hundred thousand people and their animals somewhere in the desert one thousand feet above sea level in the mountainous Afghanistan.

Further north, as in the depths of a forest, or like an oasis in the desert, lies Herat. This thousand-year-old city has been at the crossroads of many caravan routes, and it has been invaded and ravaged by many. It has been great, strong and powerful. Rich and full of life. It was destroyed but has always risen as a phoenix. When Djengis Khan, the terrifying Mongol, came here for the second time in the twelfth century, he crushed the whole city and killed everyone. Yes all, apart from forty people. So speaks the myth.

The ruins of the citadel can be seen today in the middle of the old town. The citadel of today, or its ruins, dates from the 16th century during the Timurid era, Herat's true bloom period. But there has always been a citadel in about the same place.

Herat is a historic city. It was the city of Alexander the Great, of Marco Polo and of Djengis Khan. And the trails of these and others are also seen today. It is not uncommon to see small blonde and blue-eyed heads as well as Mongolian. Yes, Herat clearly carries the results of crossing cultures.

What makes a rich and active civilization here is the Hari Rud. The river. The river that flows through the area and inspires life. In a country where brown is such a dominant colour, the green oasis of Herat gives breath and inspiration to poetry and love. Herat was, and has always been, the intellectual capital of the country. Tajiks, the people of Herat are a Persian people known for their intellectual interests. Tajiks are the dominant people in this part of Afghanistan, but on the streets, one also sees the Hazera, a Mongolian people, and some Pashtuns who dominate more in the eastern districts of the country.

Herat is a city, an active city that works in the same way it has always done. Admittedly there are some cars and other modern objects, but a little strange is to think that this city of 90,000 inhabitants works without electricity for 18 of the 24 hours. That is, from midnight to sunset the power is turned off. I may not think so much about it, my life as a traveller is probably less dependent on power, but Afghanistan is one of the world's poorest countries measured by GDP per capita. The yardstick of economic and material prosperity.

And in Herat you stopped. Herat was a city that reflected a people of pride and honour. Pride is part of the lives of the Afghans. The Afghans never had any colonial rulers who left behind infrastructure and industry. And maybe that is Afghanistan's wealth: the independence. Always rulers of their own house. The British never manged to conquer this land, even though they tried several times. An attempt by a British expeditionary force of over sixteen thousand soldiers in January 1842 was surrounded and wiped out by Afghan warriors. Only one British soldier survived to tell the horrifying story.

The Afghans meet in the tea house. That is the men. Each street corner has its chai kana – tea house. Inside sit turban-clad men with their water pipes and tea samovars. Here the conversations, the big discussions, take place. The exchange of ideas and opinions. Here you also find advice and regulations. And in the tea room, the Afghan folk music fills the ears and the heart with its melancholy and longing sound, as a reflection of the Afghan landscape. Here you feel at home, far away from decadence.

“Khub sahid?” Are you OK?

“Allah akbar!” God is great.

The Afghan is polite. The harsh men in the turban and beard look frightfully friendly. Behind sandblasted wrinkles and powerful moustaches, I meet a peaceful soul. Five times a day, the Afghans spread their prayer mats towards Mecca with the call of the mosque muezzin. La ilaha illa Allah. Muhammad Rasul’Allah. There is no god without Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet. The Afghan is a religious being. Islam is not just faith. Islam is a way of life. Based on other assumptions and values that is difficult for a northerner to understand. But people take care of each other.

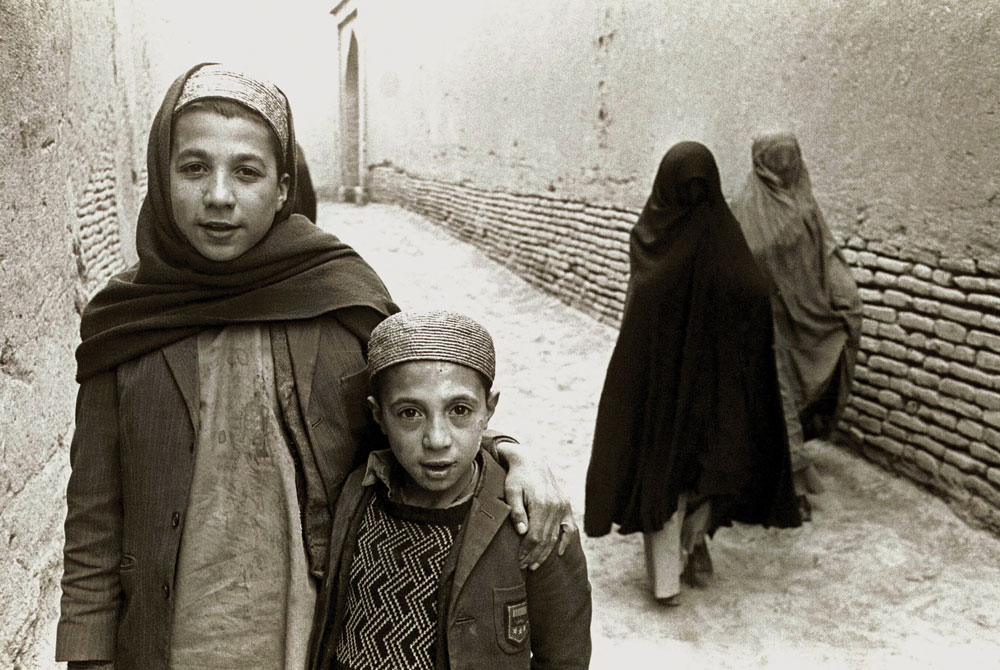

Outside, on the streets, women pass in their tent-like burqas, called chadri here. Zulfiquar, the host, has noticed my curiosity, pouring tea from his samovar and explaining smilingly: “We protect our women. They must not be attacked by strangers. In our country, family ties are strong. In difficult situations everyone can get help from their family. The ties between men of the same genus are particularly strong. My brother is not only my brother, but also my cousin. We usually marry our cousins, it is common. This way we tie the family ties closer together. A person without relatives is without help. Children without parents are for a disaster to rain.”

Watching the life go by in one of the oldest cities of mankind arouses associations and thoughts of the remnants of a medieval culture that was once here. The Afghanchadri style of burqa has been worn by Pashtun women since pre-Islamic timesAlong the grey walls of the narrow back streets of Herat women move around with rapid footsteps like mysterious ghosts. The chadri covers her from top to toe – alas, in front of her face there is a small crocheted hole through which eyes can see but not be seen.

How beautiful these Afghan women are, I will never know!

[From my diary: Herat 10thof November 1977]