My Nepali family

On my first visit to Pokhara back in 1977 I acquainted a young man called Ramjee. Being the oldest son in his family he had to look after his two younger brothers and two sisters together with his mother. He was able to make a few rupees extra by guiding Western tourists around the sites of Phewa Lake and the surrounding areas of Pokhara.

We kept in touch by letters–or snail mail as it is called these days–and I always visited him on my subsequent returns to the beautiful Himalayan Kingdom. In the spring of 1979 Ramjee accompanied me on a trek towards the Annapurna Base Camp and together we did a three weeks’ tour of Northern India–visiting Varanasi, Taj Mahal and Agra, New Dehli, and the hill resort town of Naini Tal.

We also travelled to Kathmandu and took a bus towards Kodari, the border town of Tibet. Back in 1979 Kodari was a quiet little place, as border crossings were not allowed.

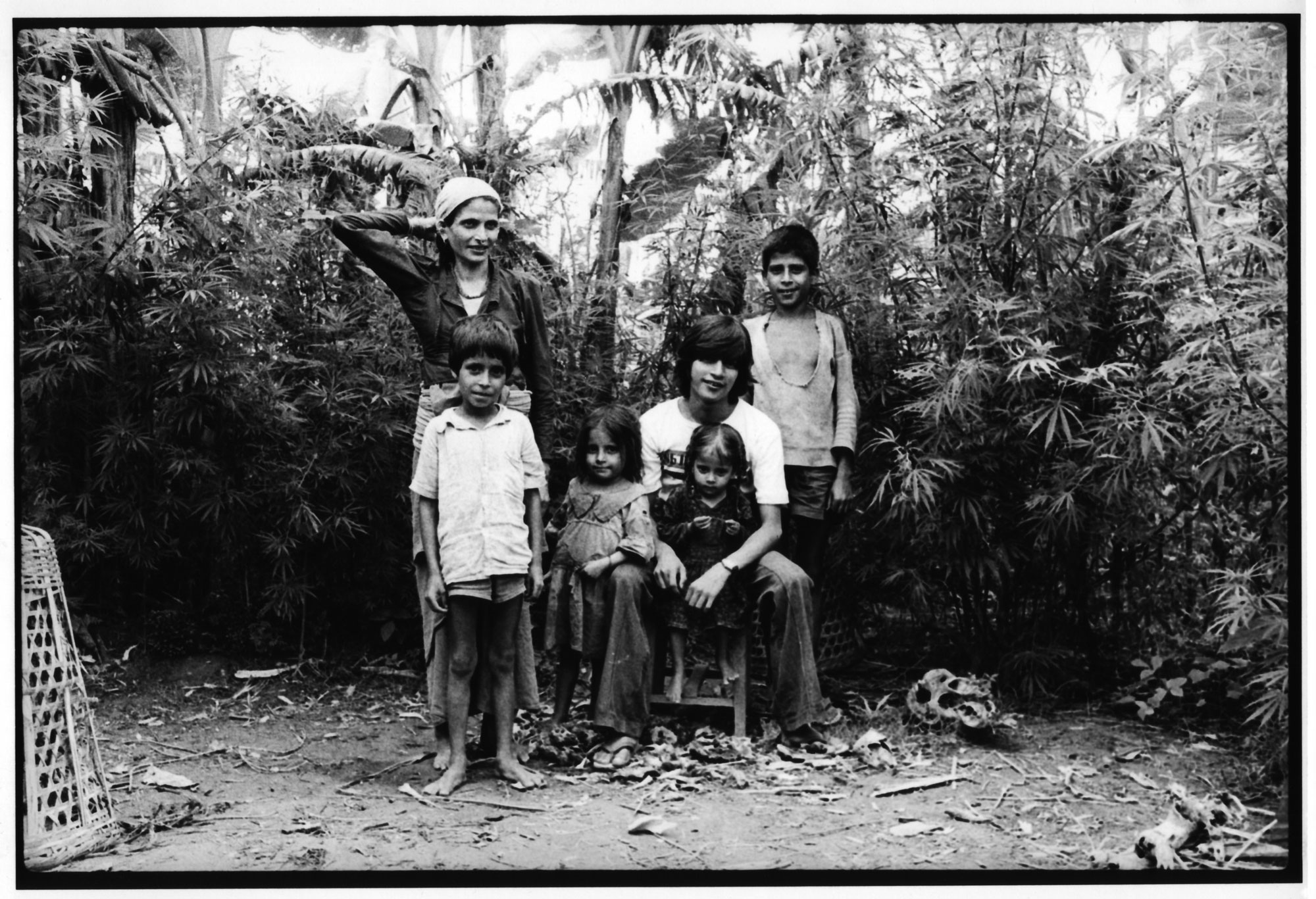

I returned again in December 1988, and by then Ramjee had married Sushila. Also, his mother had added another member to the family; his youngest sister was not born back in 1979. Ramjee was making a living out of selling used books and other basic provisions. The family is seen in the top picture.

In 1979 Baidam, which is the name of the village by the Phewa Lake outside Pokhara, was a quiet little village. There were a number of hotels, but they were all basically catering towards the lower segment of the backpacker traveller.

The flare and atmosphere of an original Nepali village with orange painted abode houses was still in abundance, and cows and cattle were roaming the few paths and streets, which of course were not surfaced. The lake, besides being the inspiration on how to relax, also doubled as bathtub and washing machine. In 1979 I stayed in a basic hotel, with no water and no toilet or bathroom facilities, and paid 10 rupees a night. At that time less than a dollar.

But alas, progress came to Pokhara too, and basically in the form of more and more [demanding] tourists. On my return in 1988, nine years on, quite a few roads were surfaced, the number of hotels had increased by ten folds, and tourism was obviously the number one business in town. Everybody wanted his or her share of the "gold rush."

Ramjee had married Sushila, and together they had the son Milan, born the year before. Later their daughter Prasna was born, and a soon after he moved his business to another part of Baidam. The turnover was not great, but somehow they managed to survive. With a little help from a friend (that's me), his children were sent to school.

Another ten years would lapse until I made my forth visit. By 1998 he had build a small house on the property he had inherited from his father, supplementing his income by renting out rooms to locals who worked in the tourist industry.

My visit in 1998 also coincided with the Teej, or women’s festival. Women’s festival in Nepal is not a political statement. It is the Hindu calendar celebration of Parbati’s dedication to Shiva. It is the time when mother and daughter travels home to mother and grandmother. It is a time when the women dance, eat, party, and pray. Without men. For five whole days. And for five whole days the men must do their own cooking. For five whole days Ramjee is without dalbhat; as instant noodles – or chow chow as they say –is the only thing he is able to cook.

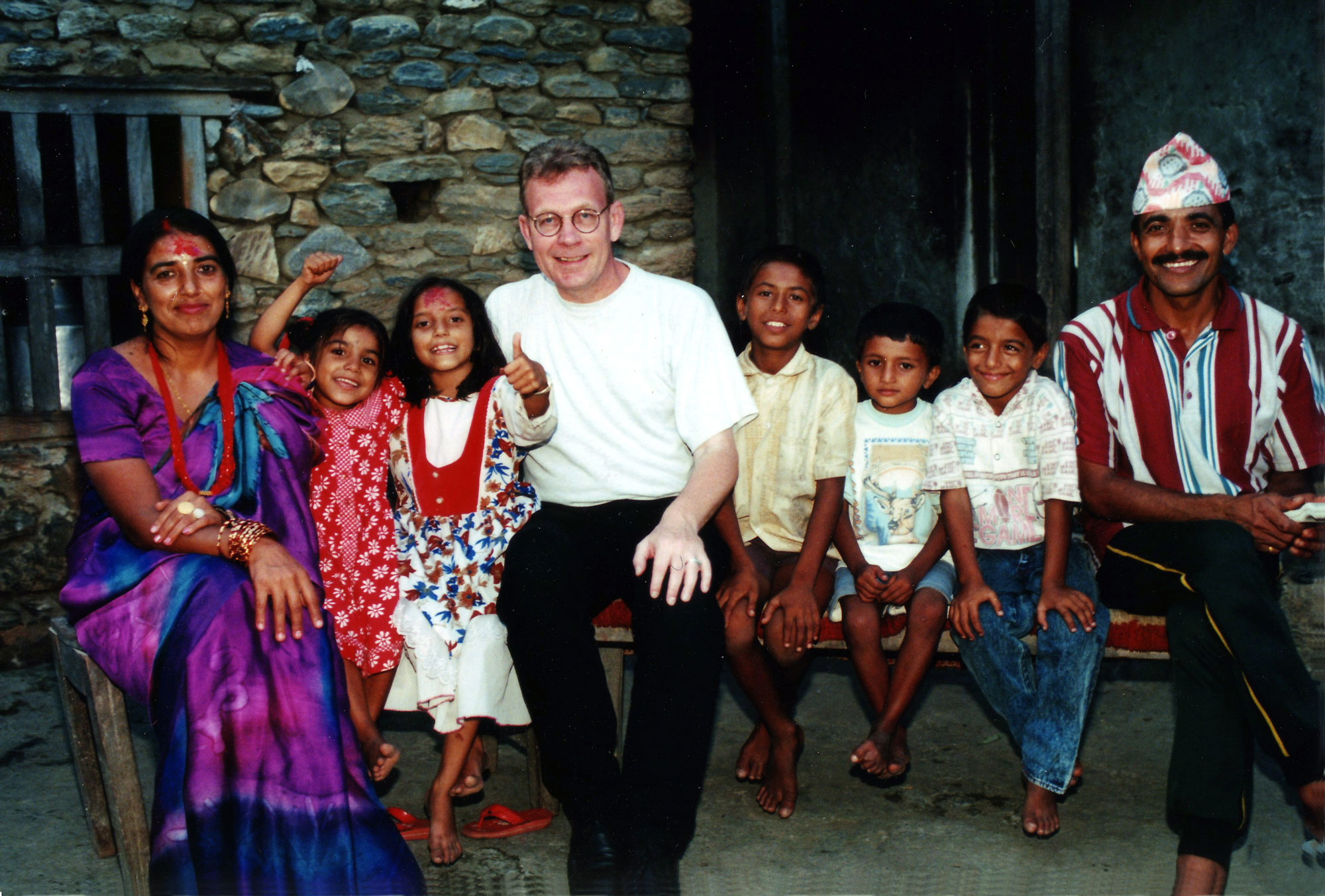

However, it was decided that the extended Pahari family (that includes me) should travel to Lalim; the village were Sushila was born and grew up. I was to meet Ramjee’s in-laws. Lalim is one hour by bus followed by two hours on foot from Pokhara, so we set out in the morning. In the picture above you can see me with Sushila and one of her brothers plus a bunch of kids. Thanks to a Finish development project, electricity had just arrived in the village. But there was still no roads, so all provisions had to be carried in from the main town on the Pokhara-Kathmandu highway, 120 minutes walk away.

Before embarking on my Kathmandu to Lhasa highway trip in 2002 I made a surprise visit, spending a week with the Pahari family. On my next surprise trip in September 2006 Ramjee had added another floor to the house and the family had moved in upstairs with separate bedrooms for the children (by now in their late teens). On the roof another room was constructed, called the Arne room, reserved for me for my future visits.

From my room I would have a fantastic view of the Machchapuchhare and the Annapurna range on beautiful days. However, September monsoon can be heavy, and this time the rain started just a few hours after my arrival and continued for the whole stay. The Pokhara airport was closed, and to catch my flight back to Bangkok I had to journey back to Kathmandu by taxi.

I made another trip again in August 2007. Despite the monsoon season, I visited some of the villages around the Pokhara valley that I haven't seen since 1979. Together with Ramjee and his wife Sushila, we walked to the Gurung village of Ghandruk, which by now has become the centre of the Annapurna Conservation Area Project. While the walk to Ghandruk back in 1979 took Ramjee and me close to three days, this time it took only seven hours. A road had been built to the village of Naypul – close to one hour away from Baidam by taxi – from where the walk took six hours. It was three hours flat, and then ascending almost 1,000 meters for the next three hours. Monsoon humidity and temperatures above 30 degrees made this walk strenuous for a man my age.

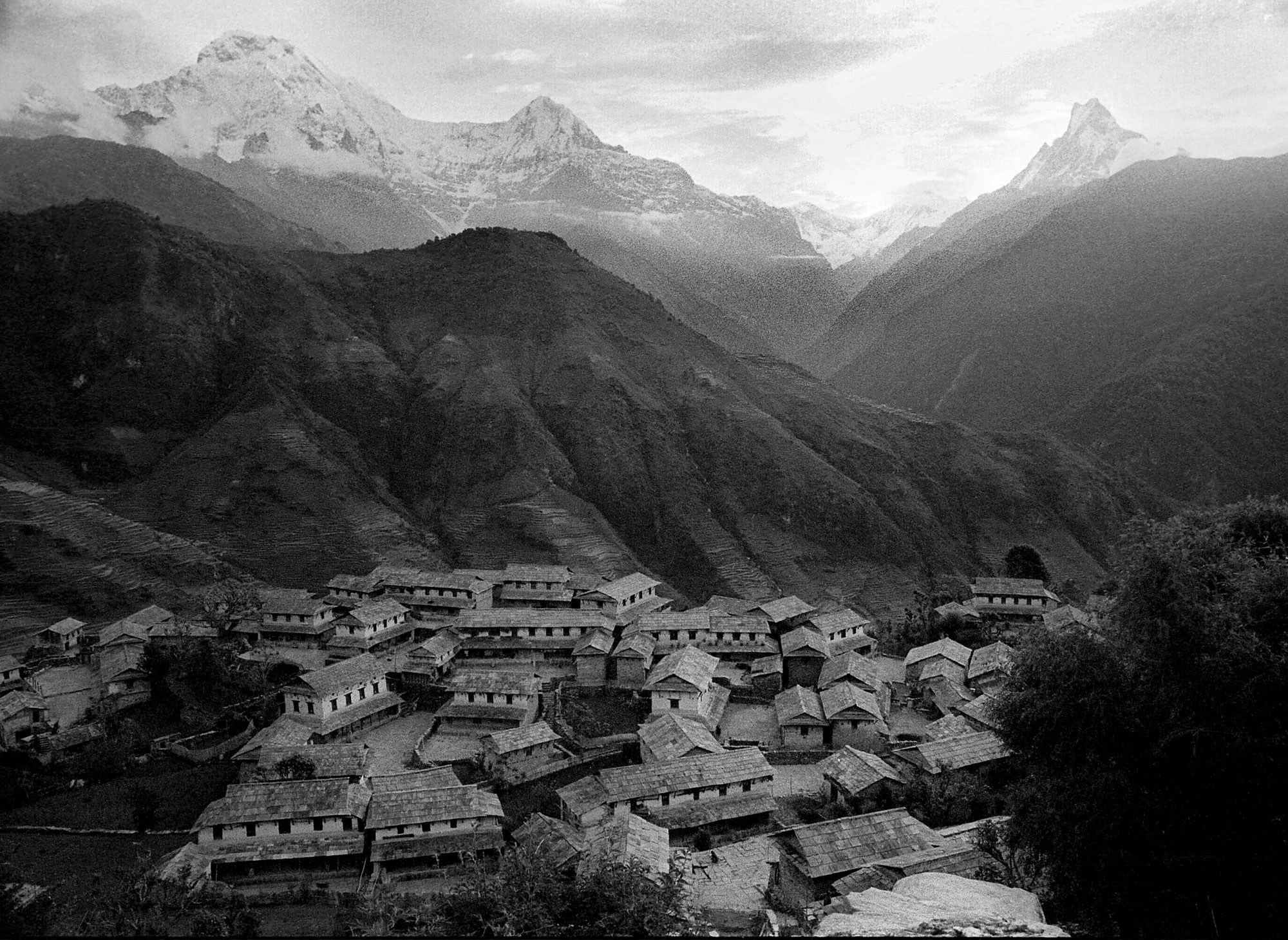

However, we arrived the village around 7 pm in the evening, just in time for the darkness to set in. While Ghandruk itself had electricity by now, on the path up to the village there was no light. Waking up in the early morning, however, a breathtaking view was what met me. The Hotel Mountain View really lived up to its name; when a few of the clouds disappeared I could catch a glimpse of Annapurna South, Hiunchuli and Machhapuchhre. In the monsoon season mornings are very misty, but both the village and the valley below were quiet and peaceful. Walking through the village in the early hours was very reminiscent of my previous visit. Apart from electric wires, a few new buildings (all guest houses), everything remained the same – it seemed. However, I could not find the viewpoint from 1979 overlooking the village, but I guessed it was probably due to 30 years of vegetation.

Ramjee’s son Milan, which by 2007 was as old as Ramjee was when I first met him, had taken over most of the communication between the family and me. As young people in most places these days, he is of course more computer literate than his parents. And communication between Nepal and Norway now mostly takes place in the form of sms, social media, and e-mail. Milan is the one who meets me when the bus [or plane] arrives from Kathmandu, and he is the one that sends me off from Kathmandu airport when I have to go home. On my last two trips he has joined me back to Kathmandu to make sure I am safely off.

I flew the whole Pahari family (less father who had to stay behind to work and look after the house) up to Jomsom in the early hours of May 15, 2008. We booked four seats on the 6 o’clock Gorkha Airways departure, and just over 20 minutes after leaving the tarmac at Pokhara airport we landed in Jomsom, around 2,700 meters above sea level. The small Dornier 228 aircraft seats 13 passengers and a crew of three, and flies between the Daulagiri and Annapurna mountain range while approaching the airstrip in Jomsom. Apparently, it is known as one of the world's most dangerous airfields and is a particular favourite of flight simulator fans. However, the landing was smooth, and the approach was spectacular with high mountains on either side of the plane. I first visited this area in 1977 when I did my first trek in Nepal – then walking was the only option, and even though the airfield was there flying was then beyond my means.

After having breakfast we settled in at Om’s Home at the northern end of the village, haggling a bargain price of 700 rupees for two double rooms. We left for the jeep stop to travel to Muktinath. Muktinath, a sacred place both for Hindus as well as Buddhists, is located at an altitude of 3,710 meters at the foot of the Thorong La mountain pass (part of the Himalayas), in Mustang district, Nepal. It was the first time visiting for us, except for Milan who had done the circular trekking route in 12 days three years earlier with some of his friends. Arriving at Muktinath two hours later I could feel the lack of oxygen at this altitude. And from the end of the road we still had to walk for 30 minutes to the temple.

Building roads to mountain villages in Nepal is an often discussed topic among trekking fanatics, both on the discussion pages of the Lonely Planet and among trekkers one meets while on the trekking paths. Some even argue that in order to preserve the original culture of the mountain people in Nepal, both roads and education beyond the very basic is a waste of time. It all leads to people leaving the villages and getting too much outside influence goes the argument.

It’s all romantic bullshit as far as I am concerned. Why shouldn’t the people of the mountains have access to the same services as we have, and why should they be denied education and modern inventions? It is ok for fat ass trekkers to walk and labour for the once in a lifetime experience, they can retreat to their comfortable 21st century life as soon as their trek is over. Would they labour as donkey caravan assistants for 2,500 rupees a month, walking the trails from sunrise to sunset, with no days off and no holidays – let alone holiday allowance? I guess not.

After returning to Jomsom in the afternoon, and spending one comfortable night, we were all prepared for the walk back to Pokhara. The road is almost complete the whole way, so we could have opted for jeep transport back to the valley, but we wanted to do the walking bit.

If you do not get off in the very early morning of the day, you will get more or less stuck in the hard blowing wind in the valley. We learned this the very first day as we left Jomsom around 11 and could only get to Marpha three hours later. Then we were so tired having walked against the strong and dusty wind. But Marpha was such a charming and cosy little village, and the locally made apple brandy was really tasteful. Because of the climate the villages in the upper part of the Kali Gandaki valley are well suited for fruit productions on a large scale. Many locals complain about missing transport facilities and lack of governmental support. Most Marphali apple farmers are in favour of the road from Beni to Jomsom. Any kind of transport other than by porter and mule would lower their cost of transportation and so raise chances to compete with Indian and Chinese apples.

Almost as soon as we checked into Sunrise Lodge (150 rupees a double) in Marpha, it started pouring down. Even though the valley is dry, they do get some pre monsoon rain too. Locals, the Thakali people being related to Tibetans, ran the charming little guesthouse we stayed in. In the old days the salt trade made the village wealthy, trekking tourism is now probably one of the major businesses in the region – even though this was hampered by more than ten years of Maoist insurgency.

The next morning, on the 17th of May, we got up at five in the morning and left soon after. Walking was easy this early in the morning, it was not too hot, the sun was not out and there was no wind. The same day we made it to Ghasa, almost ten hours later, and again the rain poured down a few minutes after we settled into our hotel rooms. All the villages along the way had apple brandy to sell, but the best quality was still the one I had in Marpha village.

The last walking leg of the trip was the four-hour walk to Tatopani, literally Hot Water, and the village from where we would use motorised transport. First of all because there is not much else to see, and secondly because we are now at such a low altitude that weather is too hot for walking this time of the year. The rain caught up with us in Tatopani too, but that was ok.

After having spent two weeks in Pokhara and on the trek, Milan again accompanied me to Kathmandu, and this time we spent three nights at the hill resort of Nagarkot. From there you can see the whole Himalayan range, including Sagarmatha (or Mount Everest), but mist and clouds are quite common in late May, so no mountain view for us. I left Nepal the day before the newly elected Constitution Assembly (or Parliament) assembled, and next time I return (in September 2008) it will be to the Republic of Nepal. Goodbye Kingdom.

I was again in Kathmandu in late August and early September 2008 to attend and co organize a workshop for LGBTI groups and organizations in South-Asia, paid for by the Norwegian Foreign Ministry. This time Milan met me at Tribhuvan International and travelled with me to Pokhara to spend two days before the workshop started. We celebrated Sushila’s birthday by eating out and watching a traditional Nepali hill dance in one of the restaurants by the lakeside. As this was in the middle of the monsoon season there were not many tourists, and so we had the whole restaurant to ourselves.

Did I notice any difference from the Kingdom I left in May and the Republic I arrived in in August? Not really, but there is a slight optimism among people, so let us wait and see if the new Nepal can deliver. Going back to Kathmandu for the workshop Milan accompanied me again, and he had a chance to meet all the delegates for the workshop. Gay, lesbian and transgender delegates came from India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan as well as Nepal, and the workshop was quite successful. I am returning again in December.

Back in 1979 when I took Ramjee with me on a three-week journey to India, this was the only country he could go to without a passport, as a Nepali passport in those days was very difficult and expensive to get hold of. We visited Varanasi, Agra, Delhi and the hill resort town of Naina Tal. It was end of May, early June, and the Indian plain was very hot. Varanasi registered 46 degrees, and that is the hottest I ever experienced (save for a visit to a sauna). Travelling with me it was the first time he travelled by train, and it gave him an opportunity to visit places, which he otherwise never would have a chance to do. He wrote a diary about his experiences, which I have kept to this day. Pictures from the journey still decorate his home. Reading through the notes I discovered that we stayed in Vishal Hotel in the Pahar Ganj area, paying 25 rupees a night for the room. At that time 25 rupees translated as three US dollars.

At the end of 2008 I invited Milan to come with me on a journey to some of the neighbouring countries, namely Bangladesh, Thailand and India. It also gave Milan a chance to travel by train for the first time, on the Death Railway – now a tourist line along the rail line built by prisoners of war as an aid to moving supplies, after the capture of Thailand by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII.

Because of my involvement with the Blue Diamond Society in Nepal, my trips to Nepal now were quite frequent. I spent Easter 2009 in Nepal, making it my 12th visit all together, rushing between meetings in various towns of the country. But I also found time to visit the Paharis. Another short visit was made in August 2009 to celebrate Sushila’s birthday and I will again visit Nepal during December.

During the summer of 2009 Milan was accepted as a student at the International Summer School in Oslo, where he did courses on International politics and Scandinavian government. This was only a short six-week course, but this was also his first visit to Europe and gave him a chance to meet students of all ages from 69 other countries.

During the second part of December 2009 I took the Paharis on a trip to India. After finishing my business in the western city of Nepalganj Milan and I met up with mother Sushila and sister Prasna in Bhairahawa in southern Nepal, close to the birthplace of Buddha (at Lumbini). From there the journey went across the border at Sunauli and on to the first big city of Gorakhpur (population 3,800,000).

We decided to hire a car from Gorakhpur to Varanasi for two reasons. Firstly, we did not want to get up at five in the morning to catch the train and, secondly, it was supposed to be quicker than the train. The choice was quite easy when it at 2,000 rupees turned out to cost only about 200 rupees more than the train tickets.

However, as the roads in this part of the world in not up to world standard, it took six hours to cover the 230 km between the two cities, and another one hour to get to Assi Ghat at the other end of the town. Driving through Varanasi was just crazy, the ultimate chaos of people, vehicles, cows, goats and sorts of animals paying attention to nobody but themselves.

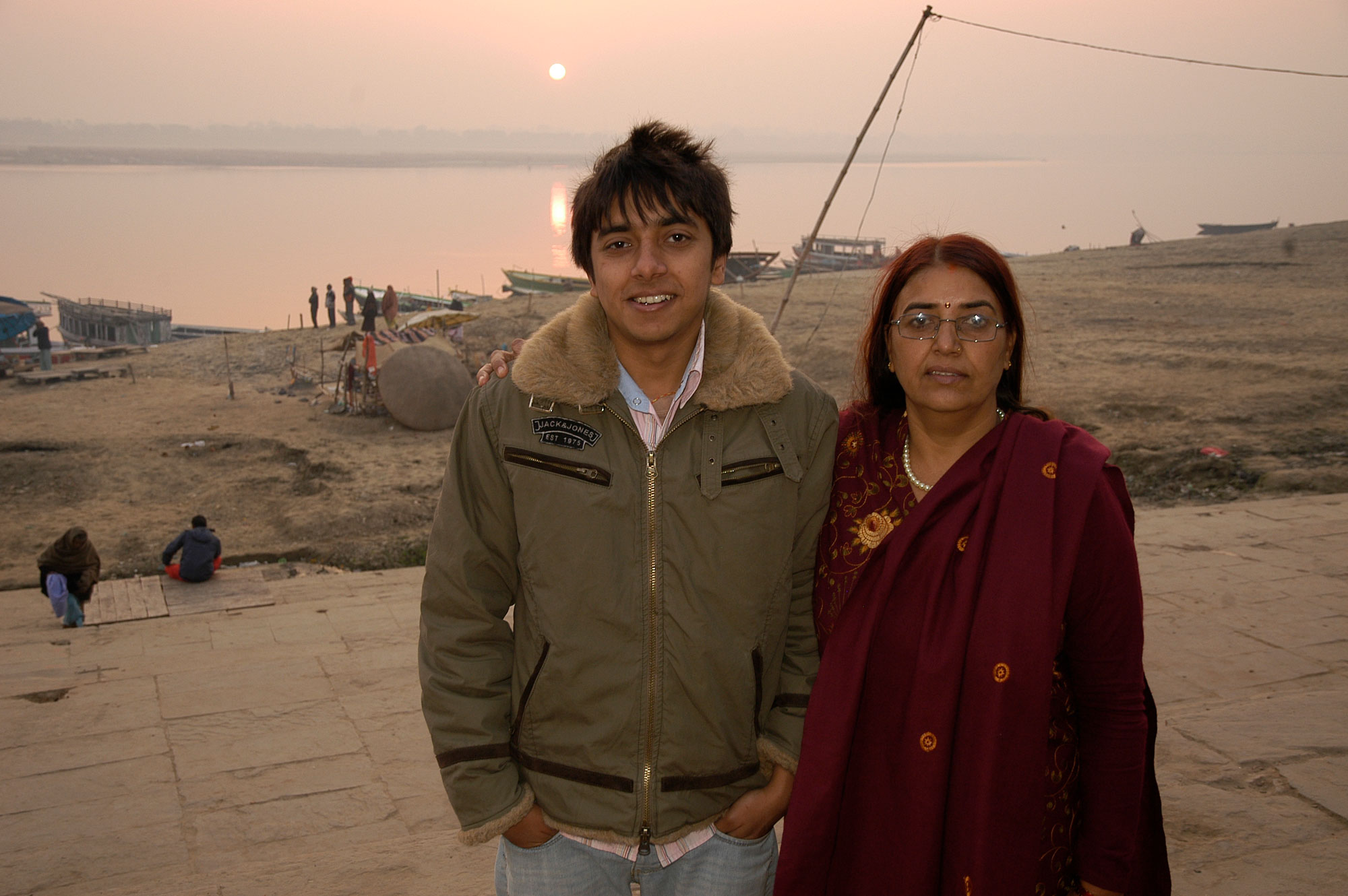

Lodging at Haifa Hotel near the Assi Ghat at 1,200 rupees a room was good value for money. The hotel provided clean and reasonably spacious rooms, hot and cold water and pleasant staff (not to be taken for granted in India), and quiet surrounding. Picture above you see Milan and his sister Prasna together with their mother Sushila.

I intended to get up early to watch the sunrise over the Ganga River on the first morning, but as usual I had troubles getting out of bed. After breakfast around 9 am we left for a walk along the Ganga- – and what a pleasant walk it was. The temperature was not hot, not cold and the sunlight was still very soft. It was quiet too, not a lot people around the ghats (can you believe that in India), but Assi Ghat is the southernmost of the 100 or so ghats along the holy river. The most crowded areas would be around the burning ghats near to Lalita Ghat.

The impressions of sound and smell cannot be conveyed through words and pictures – which are the only ones available to me. But, smell (good and bad, mostly bad) is an integral part of the Indian experience. As cows and goats roam streets and narrow lanes at free will, the stench of cows urine is there as a part of the experience. Humans too, seem to take no notice of what other people might think, as they both urinate and defecate wherever they please.

Varanasi (population 3,200,000) is a holy city in Hinduism, being one of the most sacred pilgrimage places for Hindus of all denominations. More than a million pilgrims descend on the city every year. It has the holy shrine of Lord Kashi Vishwanath (a manifestation of Lord Shiva), and also one of the twelve revered Jyotirlingas of Lord Shiva. Hindus believe that bathing in Ganga remits sins and that dying in Kashi ensures release of a person's soul from the cycle of its transmigrations.

We stayed in the holy city for four nights before returning to Nepal. On our way back we travelled on the train, giving both mother Sushila and daughter Prasna the opportunity to travel by train for the first time. The Gorakhpur Express took only three hours and a half, both leaving and arriving on time. Believe me. On the way back to Pokhara we also made a brief visit to Lumbini in the Terai, to visit the birthplace of Buddha.

As of early 2019 I have made a total of thirty visits to Nepal, each time going to stay with the Paharis. Milan is now married and has completed his Masters in Business Administration and works as a banker. Prasna is about to complete her Masters, and Ramjee has retired from his job as a technician at Radio Nepal. Their house in Baidam has been extended to a hotel and is outsourced to a local and named Maharaja Hotel.

[March 2019]