Take Me There, Country Road

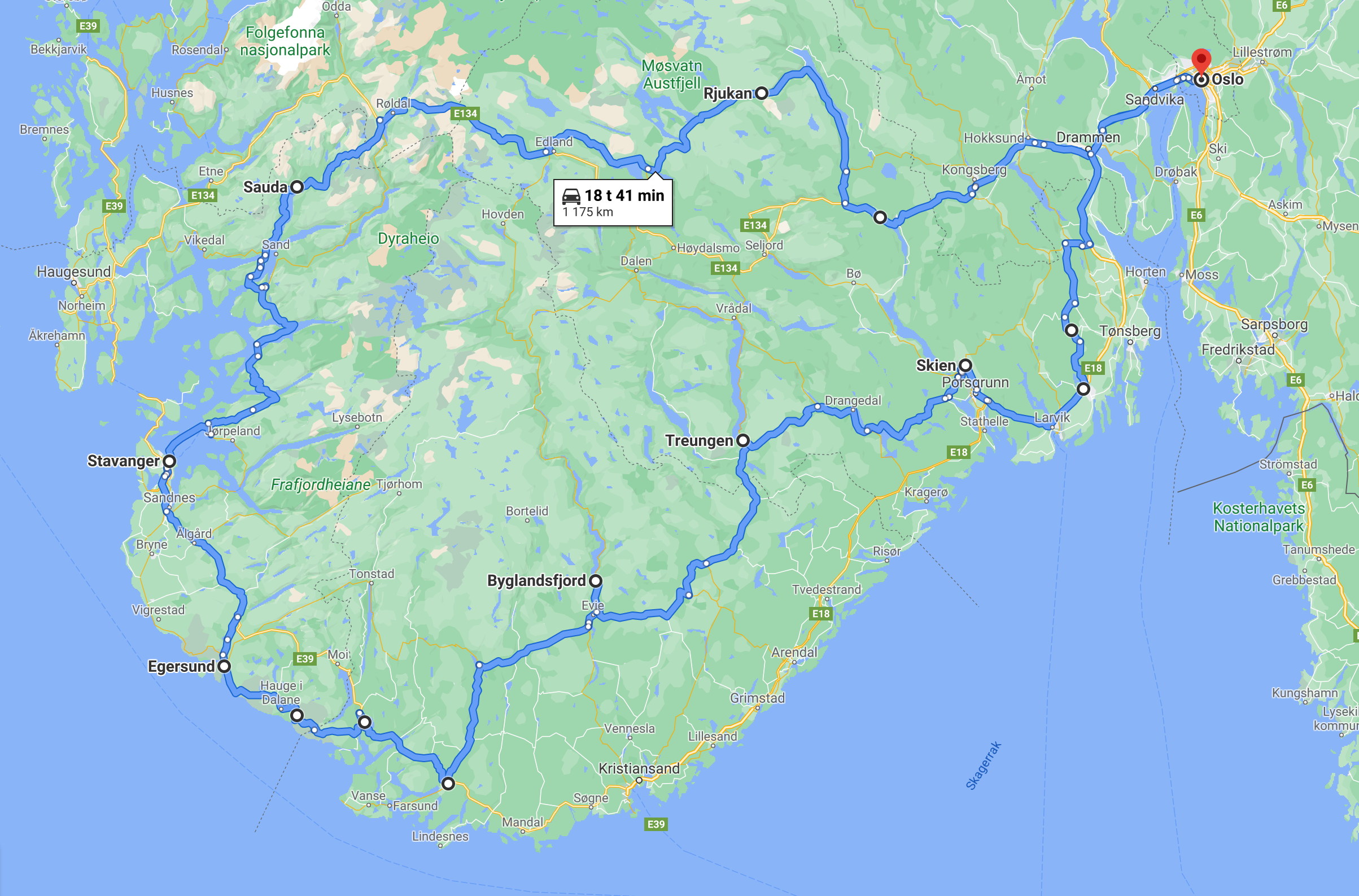

With international travel restricted due to the Covid situation we took to the road with our rented car this summer, just like last summer. Setting out from Oslo, our home, we aimed at Stavanger on the south-west coast across the mountains and returning along the coast.

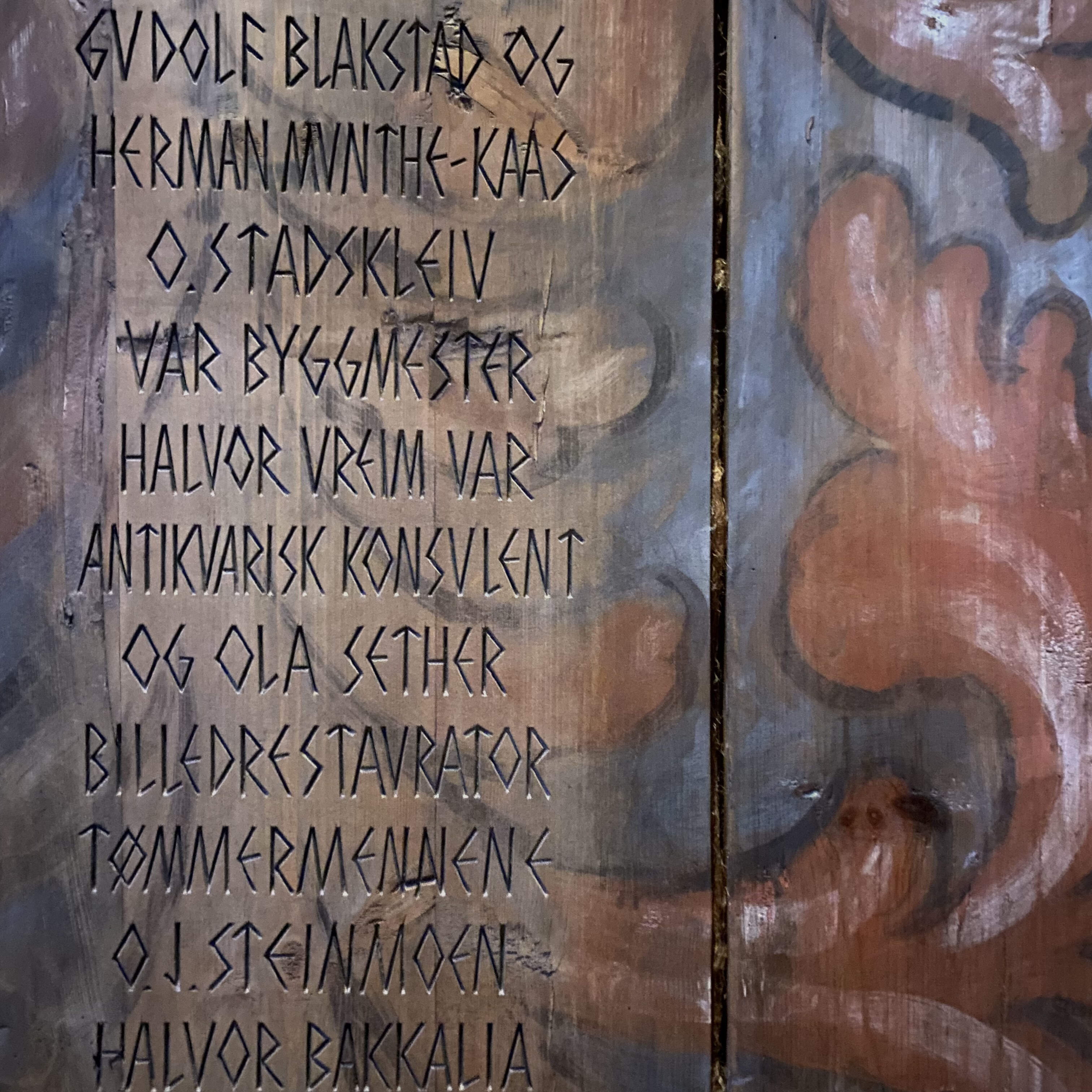

Our first stop on little tour around southern Norway is Heddal Stave Church, about two hour’s drive from Oslo. The largest stave church in the country, originating around AD 1250.

A stave church is a medieval wooden Christian church once common in north-western Europe. The name derives from the building's structure of post and lintel construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing ore-pine posts are called stafr in Old Norse (stav in modern Norwegian). The building material is ore-pine, and the wood is naturally impregnated from the fatty substances in pine. The guide at the church told us this was done by chopping off the top of the tree, and letting it stand on its roots for 10 to 15 years, so that the sap is sinking into the wood making it ready for use when chopped.

At one time there were around a thousand stave churches in Norway. Only 28 are preserved today. The Heddal stave church is still in use for weddings and christening and every two weeks there is an ordinary Sunday mass.

The next stop on our little journey is Rjukan, a quaint little town set deep in a valley, with the majestic Gaustatoppen on one side. It is said that from the top you can see the whole of southern Norway on a clear day. Situated deep in a valley also means that the sun cannot get above the surrounding mountains during wintertime. This is compensated with some gigantic mirrors high up on one of the mountains that reflects the sundown to the inhabitants during the winter months. To the joy of the around 3,500 people that live here. Also, Rjukan is a UNESCO industrial heritage site.

Rjukan was a significant industrial centre when it was established in the early 1900s, when Norsk Hydro started saltpetre production there. Rjukan was chosen because a 104-metre waterfall provided easy means of generating large quantities of electricity. Fertiliser production was moved to another town, but Rjukan (population 3,350) is now home to Norwegians Industrial Workers Museum where the history of Rjukan and a history of Industrial labour is displayed, in addition to history of the war and the sabotage connected to it. The sabotage during World War II prevented the Nazis from attaining heavy water needed to produce an atomic bomb. The sabotage is portrayed in the 1966 film The Heroes of Telemark starring Kirk Douglas in the lead role.

In Rjukan we ate in a Chinese restaurant with the conspicuous and not Chinese like name Scolopendra. A scolopendrium is a centipede, some lower classification of this species is said to have healing properties, a giant scolopendrium is regarded as highly poisonous. The food wasn’t too bad.

We arrived Sauda at 6 pm in pouring rain after a day of driving across the mountains from Rjukan. Due to maintenance work on the major tunnels at Haukeli, traffic was conducted in a convoy along the old road, one way at a time.

The mountain scenery made for many stops for viewing and photography and a short stop for coffee and sandwiches at one of the many outlets along the way.

We also spent a short time looking at the Røldal stave church, also from around 1250, but this was a much smaller and simpler church than the one in Heddal. The road from Røldal to Sauda, however, was scenic and spectacular. A narrow and winding road climbing up to around 1,000 metres above sea level before descending to Sauda at sea level. Littered with small lakes, creeks, and waterfalls the road took you through a naked landscape with views to more greener pastures deep down below. At places the road appeared almost cut out as a shelf in the mountain side, a ride is not for the faint hearted.

The town and the surrounding mountains as well as the fjord are shrouded in mist and with raindrops falling on grass outside the Sauda Fjord Hotel. We decided to dine at the hotel, whose dining hall was very quiet. Then relaxing in the lounge looking over the fjord listening to Arthur Rubinstein and Piano Sonata No. 14 In C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2 "Moonlight": I. Adagio Sostenuto.

Sauda is small industrial town at the bottom of a fjord and trading centre for the surrounding region. In 1910, the American company Electric Furnace Company (EFP) began the construction of Europe’s largest smelting plant here in Sauda. This could only be done because of the large number of waterfalls and rivers that made it possible to build power plants build situated a short distance from the smelter, which uses large amounts of electricity.

Though traditionally a farming village, this is now over, and the people of today still live on the foundation of the new town that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century.

We were welcomed to Stavanger with pouring rain, even if the nearly 150 km long drive from Sauda saw both beautiful landscapes bathed in sunshine, and sudden downpours. Changing weather indeed. Just as varied was the road, in parts wide and straight, in parts narrow, steep, and winding and in some places carved out of the mountain side like a tiny shelf. Tunnels and ferries are also part of the drive, and the last leg into Stavanger was a 14 km four lane highway underneath the sea, descending to 384 metres below sea level.

Stavanger counts its official founding year as 1125, the year the Stavanger Cathedral was completed. Stavanger's core is to a large degree 18th- and 19th-century wooden houses that are protected and considered part of the city's cultural heritage. It makes an interesting walk, even in the rain.

Stavanger is also the oil capital in Norway, and as such the city is among those that frequent various lists of expensive cities in the world. Indeed, Stavanger has been ranked as the world's most expensive city by certain indices.

Despite the rain, the temperature is still pleasant at around 20 degrees.

This morning, before the rain poured down again, we spent walking through Gamle Stavanger, a historic area of the city. The area consists largely of restored wooden buildings which were built in the 18th century and at the beginning of the 19th century.

In the aftermath of the Second World War a new city plan was created for Stavanger. It included razing most of the old wooden buildings in the city centre and replacing them with new modern structures in concrete. Fortunately, the voices against were heard.

South of Stavanger you’ll find the largest flat lowland area in Norway. The area, known as Jæren, is flat compared to the rest of the very mountainous Norwegian coast, and it has sandy beaches along most of the coastline. It is also known for being very windy, and traditionally a farmland area producing milk and meat from pork, sheep, and cattle. The area is also littered with prayer houses, as layman preachers with their congregations abound.

The Nobel Literature Prize nominee Arne Garborg hails from this area, a writer whose novels are profound and gripping while his essays are clear and insightful. Wikipedia describes him as a writer whose work tackled the issues of the day, including the relevance of religion in modern times, the conflicts between national and European identity, and the ability of the common people to participate in political processes and decisions.

The area stretches almost all the way down to the small town of Egersund, where we will spend the night at the Grand Hotel. Egersund’s culinary attractions, apparently, are one Indian restaurant and two Chinese.

Yet another wet day with clouds hanging low. We arrived the small town of Egersund yesterday afternoon after travelling down Jæren with the windscreen wipers working ferociously most of the time. As we were approaching Egersund the landscape changed from rich farmland to more barren rocks.

Worth seeing, if that sort of things interests you, is a visit to the Magma UNESCO Global Geopark. When I Google, I find out that 1,500 million years ago, the region had a landscape of red-hot magma and high mountains. Through millions of years, glaciers helped to form the landscape we see in the area today. The main rock type is anorthosite, which is more common on the Moon than on the surface of the Earth.

Egersund is another small Norwegian coastal town (population 11,484 according to Central Bureau of Statistics) that goes dead after shops close at 5 pm.

We spent last night at the Grand Hotel in Egersund, the notable establishment started by one Carl Fredrick August Post in 1869. Post was born in Prussia in 1831, trained as a mason and emigrated to Sweden and later to Norway. He married Anne Marie Hansen from Hakadal, and they settled down in Egersund in 1863. He soon became a central person in the local community and bought over some properties and started a hotel and a liquor store. The hotel soon became a central point of entertainment in the town, where in his big hall he would organise theatre performances, concerts, dioramas, art exhibitions, and exhibitions of cannibals. Tickets were sold for 35 øre for a seat and 25 for standing. Children were allowed in for 15 øre. He also rented the hall to the Salvation Army, whose main goal at the time was a crusade against “sin, death, and devil.”

Post became a frequent contributor to the local newspapers like Egersundposten and Dalane Tidende and he published his own poems, which he called “things” in a language mix of Norwegian, Swedish, and German. He later sold the hotel to a Swede; Herman Danielsen in 1878. Post continued in the property business, and he passed away in 1901.

One of the attractions in the area is Trollpikken. Trollpikken (the Troll’s Dick) is a rock formation jutting out from a cliff face to a height of almost 12 metres (39 ft) resembles an erect penis. In June 2017, the rock was severed using power tools; it was reattached the following month after a crowdfunding campaign. It requires a trek from the nearest road.

We left Egersund in the morning among raindrops and mist, taking the County Road 44 to Flekkefjord. A distance of only 66 kilometres, but with the road passing through some interesting landscape the trip took nearly three hours. The narrow road winds through barren landscape, with steep climbs and short tunnels, and invites you to make many stops to enjoy the scenery and take photographs - despite the drizzle and low hanging clouds.

One spectacular spot along the road is the descent down to the Jøssingfjord. This fjord is well known as the location of the World War II-era Altmark Incident. Around two months before the Nazi occupation of Norway, prisoners taken from the German tanker Altmark were freed by the British destroyer HMS Cossack. After this incident in the Jøssingfjorden, the term Jøssing came to mean a Norwegian patriot, the opposite of a Qusling (or traitor).

Another interesting spot is the village of Åna-Sira, at the mouth of the river Sira where it flows south into Åna fjord (hence the name of the village). It also marks the border between the counties of Rogaland and Agder and a short ride to the coastal town of Flekkefjord, where we made a swift stop for a quick stroll in the rain.

We moved on for a quick lunch at the small town of Kvinesdal (population 5,984), also known as the evangelical capital of Norway. Every summer thousands of Christians of all faiths gather at a Summer Camp, organised by Troens Bevis (Evidence of Faith) in Kvinesdal, also known as the Valley of Saron.

After having left the village of prayers we crossed the hills of Storskogen on a lonely and narrow road, and suddenly the sun appeared, and temperature rose to around 20 degrees.

We continued northwards to spend the night in Byglandsfjord, a small village at the lower end of the Byglandsfjord lake in the Setesdal valley, populated by 355 individuals.

Again, we woke up to a day with low hanging clouds. The top of hills across the lake from our room (with a view) were all covered in mist. A travel tale from Norway will also always be a travel tale of sun and rain.

The small village of Byglandsfjord (altitude 208 metres above sea level) was once the terminal station of the Setesdal Line, a 78 km narrow gauge railway line from the town of Kristiansand. It connected with a steamboat on Lake Byglandsfjorden to go further north and opened in in 1895. The railway line was closed in 1962, but parts of the railroad have been preserved between Røyknes and Grovane Station.

The Historia Norwegjæ, a short history of Norway written by monks in the second half of the 12th century, reports that the Setesdal Valley was then part of the law district "Telemark with Råbyggelag". A Raabygger or Råbygger is one who lives in a corner; this is an apt description for the valley of Setesdal, which runs like a wedge into the heights of the mountain called Haukelifjell.

From Byglandsfjord and northwards one historically finds more radical change in dress (folk costumes or bunad), architecture, dialect, folk music, dance (e.g., the ganger, a form of local village dance), customs, and cuisine, a travel brochure in the lakeside hotel told me.

On the way out of the area we made a stop at Odden Hage, a quaint little garden with a fishpond (with fish), Chinese bridges, plants, trees, and flowers. Entrance NOK 40, pay by Vipps.

As soon as we left Evje we hit a lonely forest road again and were met with a ferocious downpour. The narrow, winding, and slippery road did not invite for fast driving, but we made it to the village of Treungen (population 546) for lunch. The local guest house provided cheap (by Norwegian standard) baguettes and other refreshments.

As soon as we reached Skien by the late afternoon it was as if the rain had evaporated. The sky was clear, and we could walk around the town in only a t-shirt. Plus, a pair of jeans of course.

Skien is one of Norway's oldest cities, with an urban history dating back to the Middle Ages, and received privileges as a market town in 1358, if one should believe Wikipedia. The town was historically a centre of seafaring, timber exports and early industrialization, and was one of Norway's two or three largest cities between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Skien is also the birthplace of the author and playwright Henrik Ibsen, probably the most important writer to emerge from Norway – although he never won a Nobel prize in literature. Many of Ibsen's plays are set in an unnamed provincial town that suggests Skien. Even though Ibsen passed away in 1907 his plays still make a difference to this very day.

July 2021.